Memorial of St. Bernard, Abbot and Doctor of the Church

Ezekiel 43:1-7AB; Matthew 23:1-12

As we just heard, Jesus got pretty tough on the scribes and Pharisees. In fact, he’s only getting started; next week we’ll hear him get even tougher. It’s easy to chalk it up to Matthew’s dislike of these men and the history behind that, but I think the Holy Spirit has a better reason for preserving these words in Sacred Scripture, one that has as much to do with us as it did with them. Jesus has put his finger on a problem that has plagued the human spirit from the beginning – hypocrisy – but has also given us a way out of it.

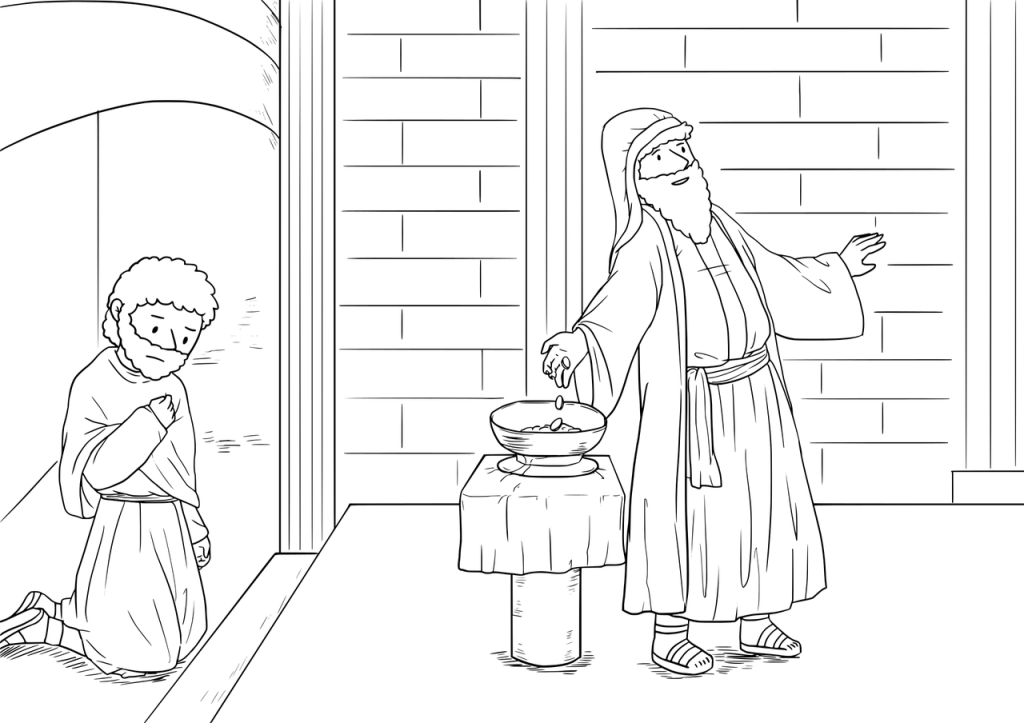

He begins by recognizing the important place of the scribes and Pharisees as teachers, and has no intention of taking this away from them or dishonoring the role of teacher. Nevertheless, he rightly reminds the people that teaching is as much about actions as it is words – perhaps more. Here, the scribes and Pharisees have a lot to answer for. Recall a few of their worst moments from Matthew’s gospel: Denouncing Jesus for wanting to heal a crippled man on the Sabbath, in a synagogue of all places (12:9); exalting their own traditions over those of God (15:1-14); and accusing Jesus of healing by the power of the Enemy (12:22-37). Our Lord sums up his reaction by quoting the prophet Isaiah: This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me (15:8).

Sadly, these words echo across the centuries. Hypocrisy is still the “go-to” accusation leveled against the Church from all sides. Always, always, the world watches Christians; it evaluates us in light of what our faith teaches, and, almost always, condemns us as hypocrites. Yes, non-believers are hypocrites, too, and yes, they can be harsh and unfair, but we must ask ourselves: Is what they’re saying true? What kind of world would it be if we were to more truly practice what we preach? Perhaps the late Brennan Manning was right when he said, “The greatest single cause of atheism in the world today is Christians, who acknowledge Jesus with their lips, then walk out the door, and deny Him by their lifestyle. That is what an unbelieving world simply finds unbelievable.”1

So, while the Divine Physician has diagnosed the disease, he also prescribed the antidote – humility – when he said, whoever humbles himself will be exalted (Matthew 23:12). By happy coincidence, we remember today the mellifluent doctor of the Church, St. Bernard of Clairvaux who, when asked to name the three most important aspects of the spiritual life, replied, “Humility, humility, and humility.” He might well have said it 9 more times, for he gives 12 steps to deeper humility in his book, Steps of Humility and Pride.

The twelfth step is called, “an attitude of pious prostration.” It is directly opposed to hypocrisy, or what St. Bernard calls “an attitude of vain curiosity.” Tempted by the pride of vanity and fear of showing others who we really are, we seek to conform ourselves to the world; to please ourselves and others, rather than God. But hypocrisy leads us only to unhappiness, for it’s pretentious and inauthentic, a lie to ourselves about ourselves. Happiness, on the other hand, is found only through humility. It is “pious” to the degree that we reverence God as our Creator, and “prostration” in the sense that we, like Ezekiel in the first reading, bow in body and spirit before His infinite glory. This level of humility is submission in two ways: First, to the truth that we, though sinners, are infinitely loved by God, not for what we can achieve, but for who we are; and second, to the grace of God that has the power to conform us more and more to His own image, if we will allow it.

St. Bernard knew all this from experience. When he entered religious life, Bernard was determined to withdraw in silence from the world and from education. However, by allowing God to form him in the humility he would come to so beautifully teach, Bernard became the most widespread, eloquent, and influential preacher and teacher of his time. What a world it would be if we, like St. Bernard, professed Jesus with our lips, then walked out the door and proclaimed him by our lifestyle.

St. Bernard, pray for us.