Solemnity of Christ the King (C)

Luke 23:35-43

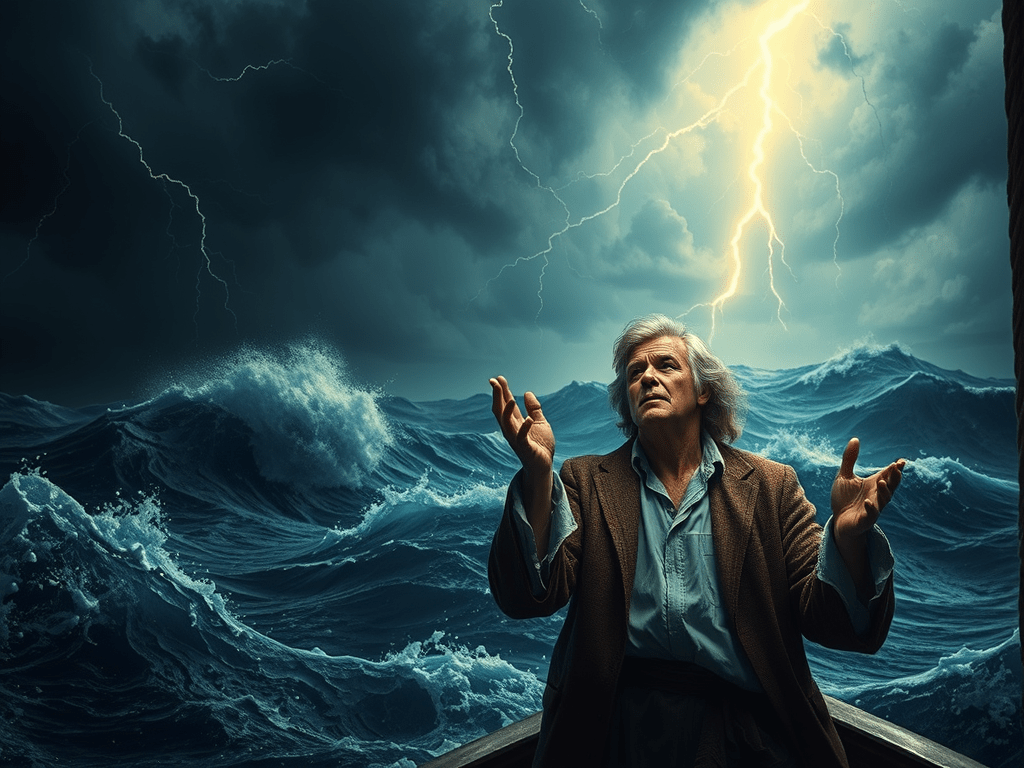

The author and theologian Frederick Buechner once said that the story of one of us is in some measure the story of us all. As we’ve seen throughout this past year, if any storyteller shows the truth of this, it is the evangelist, St. Luke.

Today is no exception. In fact, it may well be Luke’s master stroke. Only he gives us a story so compelling, so poignant, so reflective of the human condition that it has come to be called, “the Gospel within the Gospel.” It is, of course, the story of the “Good Thief.”

But again, like so many great stories, it’s about much more than one thief. It’s also about the other thief, the soldiers, the rulers, and everyone gathered around or even passing by the cross. It is, as Buechner said, the story of us all.

Although the action involves each character in the story to some degree, and we can see ourselves in each of them, Luke focuses our attention on the two thieves. It’s easy to see why: like Jesus, they suffer on crosses of their own, and they, too, will die that day. Above all, and without their understanding it, both men will come face to face with their King.

The difference between them lies not in their suffering, but in their hearts. The heart of the first man is intent on escape. While this is natural, people who want something so badly can end up bullying others – even God – desperate to get what they want.

I might ask, ‘How is that like me?’ – but I already know. Many times, I have approached the Lord with a similar attitude. “What kind of God allows bad things to happen? You can do it, so get me out of this!” That isn’t a prayer, it’s a demand, and it betrays a heart looking for God to fix the outer situation, not the inner person.

Note that Jesus does not reply to this man. It’s natural to want relief from our cross, and to ask for help with it, but it’s arrogant to make demands of God or measure His Kingship by how well He makes us content and comfortable.

By contrast, the second thief accepts the truth about himself (we are getting what we deserve) and Jesus (he is innocent and is entering his kingdom). In that humility, all he asks is that Jesus remember him.

This is our ideal. We are like the good thief every time we approach the Lord not in arrogance but in humility and truth. Our best, most effective prayers are said in trust — acknowledging our sin, our need for mercy, and our faith that even in the worst of our suffering, Christ the King is Lord of all and has our good in mind.

Of course, our hope is that Jesus replies as mercifully to our prayer as he did to the good thief. Luke is clear that our Lord is not outdone in generosity! Where the thief said, Remember me, Christ replied, You will be with me, and where he said, when you come into your Kingdom, Christ said, Today.

Today and every day, Christ the King stands between those who approach him with pride and resentment on the one side, or humility and repentance on the other.

So the question is, which side of the King do I tend to stand on?

—