1 Thessalonians 2:2b-8; Matthew 9:35-38

During a parish mission years ago the homilist asked the congregation, “Do we live the Christian life as sheep or shepherds?” At the risk of oversimplifying, his point was that being a true follower of Christ requires us to be both. Key moments from the life of St. Augustine of Canterbury beautifully illustrate that point.

The first occurred on the French side of the English Channel in the late 6th century. Reality had taken hold; Augustine, the leader of a group of 40 Benedictines sent by Pope Gregory the Great to re-evangelize England, learned from the locals that across those choppy waters lived not only pagan but also hostile Germanic tribes. If they landed, they stood an excellent chance of being killed.

So at that moment, was Augustine a sheep or shepherd? We might think “sheep” when we hear that he sent men back to the Pope to ask if the mission should be abandoned. Is he a coward? Shouldn’t he obey orders no matter what? Perhaps, but perhaps it’s prudent for a sheep to pause if he thinks he’s walking off a cliff. Better still, perhaps as the shepherd of 40 missionaries it would be foolhardy to blindly go forward if the pope did not know what Augustine now knew.

Like the balance between sheep and shepherd, the virtues are also a balance, in this case a balance between extremes. For example, courage is the virtuous balance between cowardice on the one hand and foolhardiness on the other. Knowing the balance is one thing, finding it another. We need the grace of God to do this; to face down our fear of rejection, failure, inadequacy, or harm. St. Paul knew this; in the first reading he says, We drew courage through our God to speak to you the Gospel of God with much struggle (1 Thessalonians 2:2). Augustine was graced with courage in abundance, for when he received the reply that Gregory wished them to set sail, he immediately did so.

His courage was rewarded. They landed in southeastern England, which was ruled by King Ethelbert, a pagan but married to a Catholic. After Augustine met with him, the king allowed them to preach the Gospel to his people. A year or so later, he himself was baptized and went on to become a saint in his own right. What’s more, when Ethelbert converted, thousands of his subjects came with him.

But a second trial remained. Although England was largely pagan, small bastions of Catholicism remained in Wales and on the western shore. The ancient remnants of Irish missionaries, these Catholics were angry that the Roman Empire had left England and abandoned them. Although Gregory wanted them reunited, Augustine was unable to do so. Some accuse him of going against the Pope’s advice, or blame him for being tactless, arrogant, unwilling to compromise, and ignorant of their culture. Did he fail as both sheep and shepherd to them?

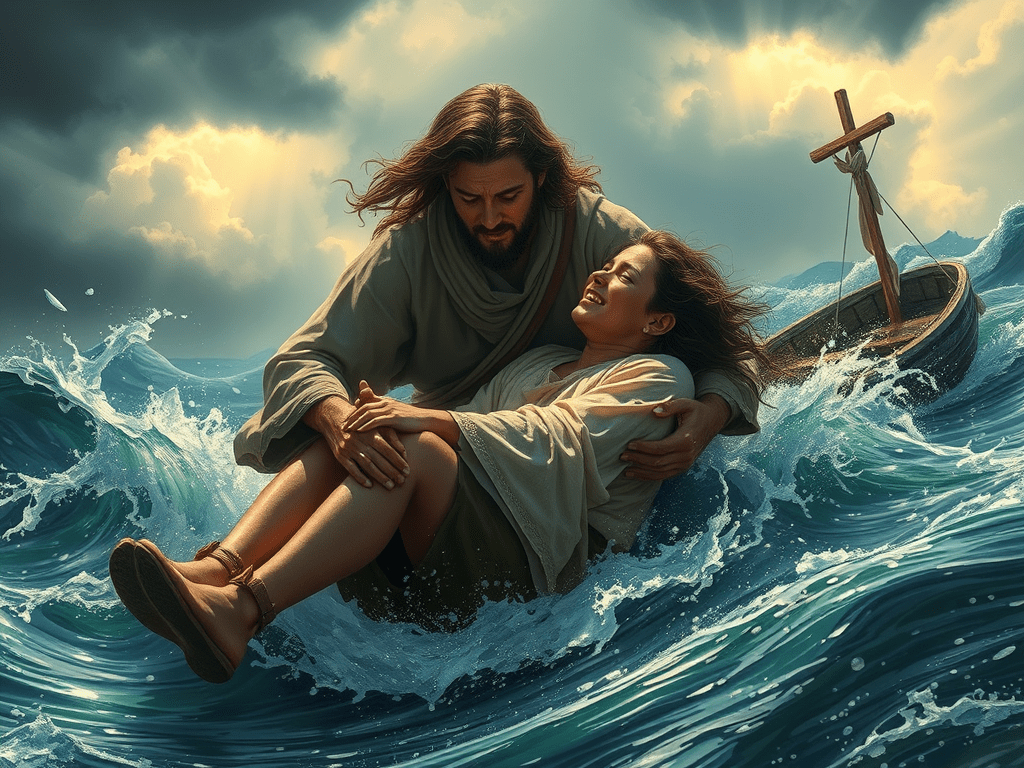

I think it’s truer to say that like Christ, Augustine saw them as troubled and abandoned, like sheep without a shepherd (Matthew 9:36). When the Good Shepherd felt pity for such a flock, he ministered to them but did not change his teaching. Similarly, Augustine may have pitied or sympathized with the Celts, but in his role as shepherd he wasn’t going to give in on doctrinal points such as the date to celebrate Easter, which these groups demanded. No good shepherd can allow the flock to set the terms for following, even if it costs his reputation and means separation. In this, Augustine was ultimately vindicated; years after his death, the Celtic Catholics were united with Rome.

The life of St. Augustine of Canterbury reminds us that the saints did not get where they are by being either a good sheep or a good shepherd; rather, they learned and they teach us how to be both.

As sheep, we follow Christ wherever he leads and do whatever he asks. This tempts us to focus on the unknown: where is Christ leading us and what is he asking? But these are the wrong questions. It doesn’t matter. All that matters is our trust that the God who leads us won’t abandon us, and that we are praying for the grace to be faithful, to follow him no matter what, for he always leads the way to victory. Like the saints, we’re only human; as Augustine showed, even saints are sometimes afraid. But he also showed that he was a sheep who knew his Master’s voice, and when his vicar encouraged him to keep going, Augustine’s faithfulness emboldened him to follow Christ beyond his fear. His obedience was rewarded with many converts.

Yet we are not only sheep, we are shepherds. This may sound odd because, as the Gospel acclamation reminds us, Christ is the Good Shepherd; what’s more, if he has vested anyone with a shepherd’s staff it is the Magisterium, the teaching authority of the Church he established. Nevertheless, by our baptism we are anointed to the prophetic role of teacher. At the end of Mass we hear “Go and announce the Gospel of the Lord;” whether by word or action, we are charged to preach the Gospel to the world. This is what Augustine did; to anyone who would listen, from kings to the lowliest peasant. No one is universally successful and Augustine lost some battles, but Christ won the war; eventually and in one of the great ironies that define the faith, England, saved by the continent, would in time send missionaries back to Europe to save it, like St. Boniface who became patron saint of Germany. None of this would have happened without the groundwork laid by St. Augustine of Canterbury, true sheep and true shepherd.

St. Augustine of Canterbury, pray for us.