The 2nd Sunday in Ordinary Time, B

Isaiah 49:3, 5-6; Psalm 40:2, 4, 7-8, 8-9, 10; 1 Corinthians 1:1-3; John 1:29-34

As we look across the Bible, certain themes tend to keep showing up. One example shows itself today; it’s something I call, “I cannot see what I am looking at.” What is that? Well, in story after story, book after book, we find that a person’s significance or calling is completely unrecognized until someone discerns and names it. Think of King David. No one – not his family, his friends, not even the great Samuel himself – realized that this unassuming little shepherd had been chosen by God to lead Israel.

There are many others – Gideon, Samuel himself, Queen Esther, Moses – showing this same pattern. God’s work is right there, people are looking right at it, but nobody sees it until someone points it out. And that someone is usually God Himself.

What got me thinking about that was the mysterious line in the gospel spoken by John the Baptist: “I did not know him.” He says it twice! But weren’t they cousins? Did the two kids never hang out? Didn’t John leap in his mother’s womb when Jesus’s pregnant mother walked in? What’s going on?

It’s that theme. John couldn’t see what he was looking at. Yes, he saw Jesus, perhaps many times, but not until the Spirit revealed it to him did he come to recognize who Jesus was. That’s why, after the Spirit descends, John says, “Now I have seen and testified…” In other words, “Now God has shown me.”

It isn’t that we’re spiritually blind or refusing to see. Rather, as St. Paul said, we see, but through a glass, darkly. Samuel saw David, God saw a king. Gideon looked at himself and saw a weak man, God saw a warrior. Esther saw a crown, God saw a champion. In every case, human eyes were open, but understanding was closed. Recognition of God’s work requires revelation, not mere human insight.

The lesson for us is simple, and very fitting for these weeks we call “Ordinary Time.” We hear the word ‘ordinary’ and think ‘plain, unremarkable.’ But ‘ordinary’ in Church time means ‘counted’ – the first week of Ordinary Time, the second, etc. In fact, Ordinary Time is far from plain or unremarkable; it’s the challenge of learning to see, with God’s help, what is already right in front of us.

What’s the challenge? Familiarity. We actually see too well. We hear the start of a familiar reading or Eucharistic prayer and are tempted to think, “Oh, I know this one,” and tune out. Or we get so used to looking at one another that we don’t see the treasure each of us really is. Perhaps worst or all, we’re so used to seeing ourselves that we look in the mirror and think, “What’s the big deal? There’s nothing extraordinary about me.”

That certainly isn’t what God thinks. Each time Scripture is read is a new time; we are different than last time, the situation is different, God is speaking to us right now, where we are. Each Eucharistic prayer brings us spiritually to the eternal moment of the crucifixion of Christ; he is dying that we might have life. Each person, ourselves and those around us are, in his eyes, infinitely precious; well worth dying for. And he loves each of us so much that he wouldn’t make the world without us.

So, we fall victim to the same trap that many do in the Bible: we cannot see what we’re looking at. And we won’t see it unless the Spirit reveals it and we are attuned to it.

Attuning to it means starting with some hard questions. What am I looking at every day but not recognizing? Where is God present around me but unnamed? Whose dignity or vocation am I overlooking — including my own?

Just as John needed the Spirit to recognize Jesus, we need the Spirit to recognize grace in even the most “ordinary” places. But we also need humility. As John said, “I did not know him,” so we might say, “Lord, I don’t always know you. Please, help me see.” That says the plain truth: Faith isn’t about figuring God out or discovering something new, but realizing how God is already here. What’s missing isn’t information, but recognition.

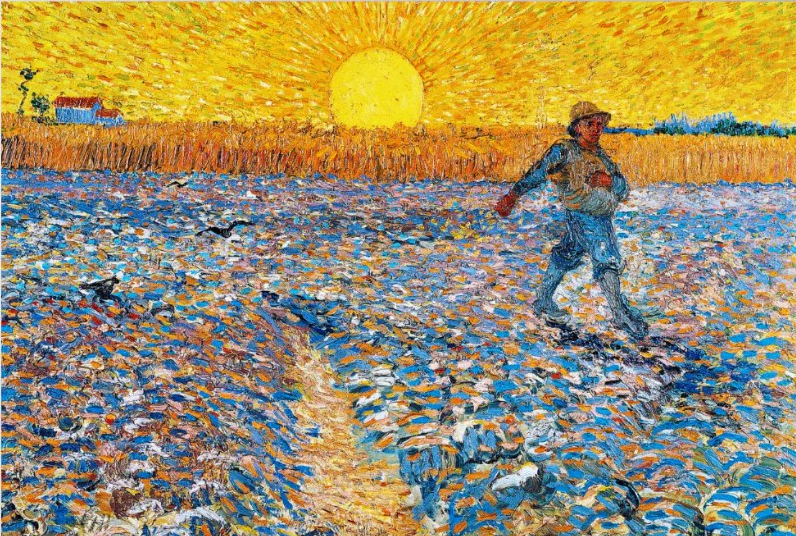

Perhaps the Baptist helps us out here, too. In a little while, we’ll hear words so familiar that they almost pass right through us: “Behold the Lamb of God.” John said that because he recognized (at last!) who was standing in front of him. Every time we hear them at Mass, the Church helps us do what John did — name what we would otherwise miss. What Father is holding is no longer bread, and this is no mere ritual. This is the Lamb who takes away the sins of the world. He is here, right in our midst.

Finally, we are meant to take that revelation with us as we go, and make it make a difference in the world. Where is Christ? He’s in the people next to us, the people at the store, on the street, at school, at work, or wherever we are. We look at them, but do we see them? And as for ourselves, when you look in the mirror, see Christ, who desires to work in you and through you.

John said, “I did not know him.” Let us say, “Lord, I don’t always recognize you, especially when you come quietly, in those deceptive, ordinary ways. Please send me the Holy Spirit again. Help me see what I’m looking at.”

—