2 Corinthians 5:14-21; Luke 10:29-37

Of all of life’s difficult questions, perhaps the most challenging concerns suffering. It can be put very simply: Why do good people suffer? Of all the saints, the one whose life most clearly poses that question is the young girl known as St. Germaine.

She was born Germaine Cousin in 1579 in Pibrac, a small village in south central France. When Germaine was just a baby her mother died. Laurent, her father, soon married a woman named Hortense who for some reason intensely disliked Germaine. It may have been because Germaine was born with a deformed arm, prone to illness, and suffered from a disease that caused unsightly, discharging lesions on her neck.

Under the pretense that she might infect others, Hortense insisted that the little girl live outside, either in the unheated barn or under the stairs. So, Germaine slept on mat, was given only table scraps to eat, and never owned a pair of shoes. By the age of five, Hortense forced her to work every day shepherding sheep or spinning a quota of wool, a difficult task given the deformity of her arm. Regardless, failure meant starvation. As if all this weren’t enough, neighbors saw her stepmother regularly beating the child.

Her one consolation was also the greatest; Germaine loved our Lord and His Mother. Denied a formal education, she taught herself enough about the faith to receive First Communion. She loved adoring and receiving Our Lord in the Holy Eucharist and never missed daily Mass even though this meant leaving the flock, which she innocently and simply entrusted to the Good Shepherd. No harm ever came to it. She loved to pray the rosary and would fall to her knees to recite the Angelus at the sound of the bells, no matter where she was. The other children noticed Germaine’s piety and would gather around her to listen as she taught them about Jesus and Mary.

Adults also noticed but dismissed her as either a lunatic or religious fanatic. Still, no one could deny her charity. Even though all she had to eat was bread, she gave it to the poor whenever she came upon them. When some townspeople witnessed the waters of a local stream part for Germaine on her way to holy Mass, everyone began to realize that God was specially present to this starved, frail, abused young girl.

Once this news reached her family, they began to repent. Her father finally put a stop to his wife’s abusive behavior and offered his daughter a place at home with the other children. In her humility, Germaine begged to be allowed to remain outside and it was there, early in the summer of her 22nd year, that her father found her. She had passed away during the night, lying on her bed made of twigs.

The life of St. Germaine is so compelling, so heartrending that we cannot help but ask again: Why would God allow such suffering to happen? I think that before we focus on God, we should use the story of St. Germaine to take a deeper look inside ourselves.

First, we cannot blame God for the suffering we willfully inflict on each other. Of her own free will, Hortense banished Germaine from the house, starved her, overworked her, and beat her. While few of us have ever gone this far, we have all found ways to hurt others. In anger, pain, or frustration, we’ve banished people from our lives, starved them of affection, demanded too much from them, and even been verbally abusive toward them. Like Hortense, they may be some of the people closest to us.

Then there is the suffering we don’t cause but also don’t do anything about. Laurent stood idly by for years and allowed his wife to abuse his daughter. On top of this, neighbors watched in silence as Hortense physically abused Germaine. They may have thought it was none of their business, but the parable of the Good Samaritan reminds us that the true neighbor is the one who shows mercy (Luke 10:35-37). Again we must ask ourselves how we are Good Samaritans to the hungry, sick, addicted, imprisoned – all the needy of our time.

Finally and most mysteriously, there is suffering that just seems to happen. No one caused Germaine’s birth defect, frailty, or skin disease. We look to God and wonder why He would allow anyone to suffer like this.

Although we cannot know the answer in this lifetime, the example of this little saint gives us some insight into it. St. Germaine did not endure suffering, she triumphed over it. Suffering was not a test given to her but a means through which she might glorify God and sanctify herself. No one likes to have misfortunes or hardships come their way, but how would virtues such as fortitude, patience, humility, or long-suffering develop without them? Without virtue, the terrible conditions in which Germaine found herself would have been a living hell; with them, they became a sanctifying fire. Thus, it was not anger or revenge but love of Christ that impelled her (2 Corinthians 5:14); for the sake of that love she drew closer to Him and in imitation of it she brought others to Him. Such is the marvelous, inscrutable way of God that Germaine would become the instrument by which Hortense herself, the source of so much of her suffering, would repent and be converted.

Let the example of St. Germaine always remind us that we are not defined by what we’ve been given but by what we give; not by who we are but by who we become; and not by our suffering but by our God-given dignity.

St. Germaine, pray for us.

Mary understood this and, as in all things, obeyed her Lord. That is why i

Mary understood this and, as in all things, obeyed her Lord. That is why i Of course t

Of course t

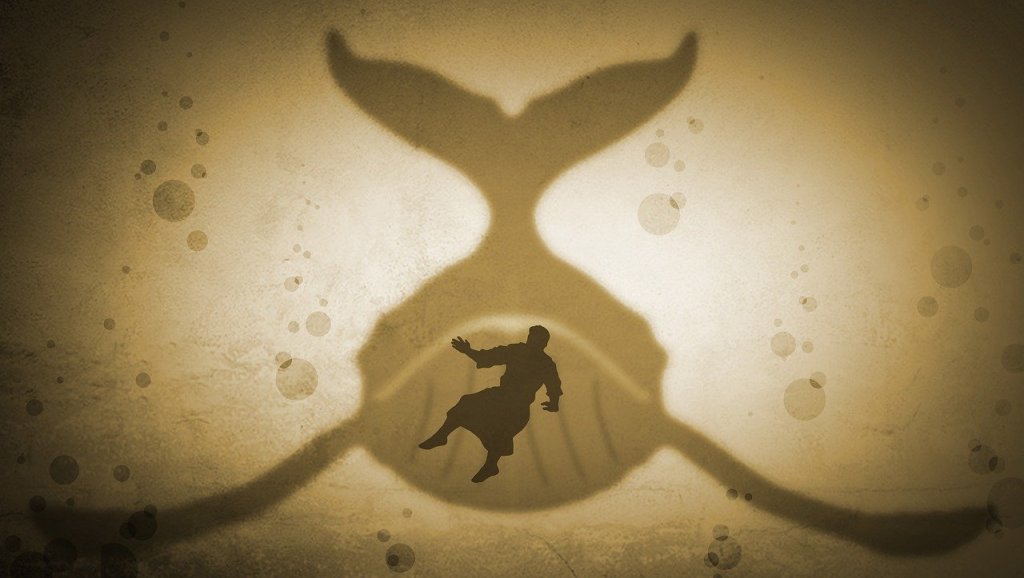

When we think of the dragon we think of the Devil and it is right to do so, for Scripture does refer to him that way (Revelation 12, for example). There is no doubt that the dragon is the Enemy but there is also no doubt that too often the dragon looks back from our own mirror. Worse yet, the victim does too; we allow sinfulness such a hold over us that in effect we devour ourselves, relent to the darker angels of our nature.

When we think of the dragon we think of the Devil and it is right to do so, for Scripture does refer to him that way (Revelation 12, for example). There is no doubt that the dragon is the Enemy but there is also no doubt that too often the dragon looks back from our own mirror. Worse yet, the victim does too; we allow sinfulness such a hold over us that in effect we devour ourselves, relent to the darker angels of our nature. The psalmist must have had Joseph in mind as he sang,

The psalmist must have had Joseph in mind as he sang,