The Feast of the Transfiguration

Daniel 7:9-10, 13-14; Luke 9:28b-36

Of the three evangelists who write of it, Luke’s account of the Transfiguration stands out in at least two ways: Prayer and the true meaning of glory.

First, Luke sets the scene with prayer. This isn’t surprising; prayer pervades his gospel. Only Luke shows Jesus praying at crucial moments – His baptism (3:21), choosing the Twelve (6:12), Peter’s confession of faith (9:18), the Transfiguration (9:28), before teaching the Apostles to pray (11:1), and his Crucifixion (23:34, 46). But it isn’t just the frequency of his prayer, it’s the power; as we heard today, it was transfiguring! This is a lesson for us. While we don’t expect prayer to transfigure us, we should expect it to transform us; indeed, the whole point of prayer is that our will, slowly but surely, be conformed to the will of God. To paraphrase St. Josemaria Escriva, the best prayer begins with, “If it pleases you, Lord…” and ends with, “… Thy Will be done.”

Luke is also the only evangelist to tell us not only of the appearance of Moses and Elijah but of their conversation with Christ and, not coincidentally, that the Apostles missed the whole conversation; they had been overcome by sleep (9:32). I wish I could say that I’d never do that, but I can’t. Far too many times, I too have been “overcome by sleep” while praying. Herein lies another lesson for us. If we find ourselves often falling asleep during prayer, we should consider changing our routine; perhaps by praying earlier in the day or making sure we are getting enough rest. As Luke is going out of his way to show us, prayer was important to Jesus; as his disciples, it is for us, too. Far better to structure our day around prayer than to allow our day to dictate our prayer time.

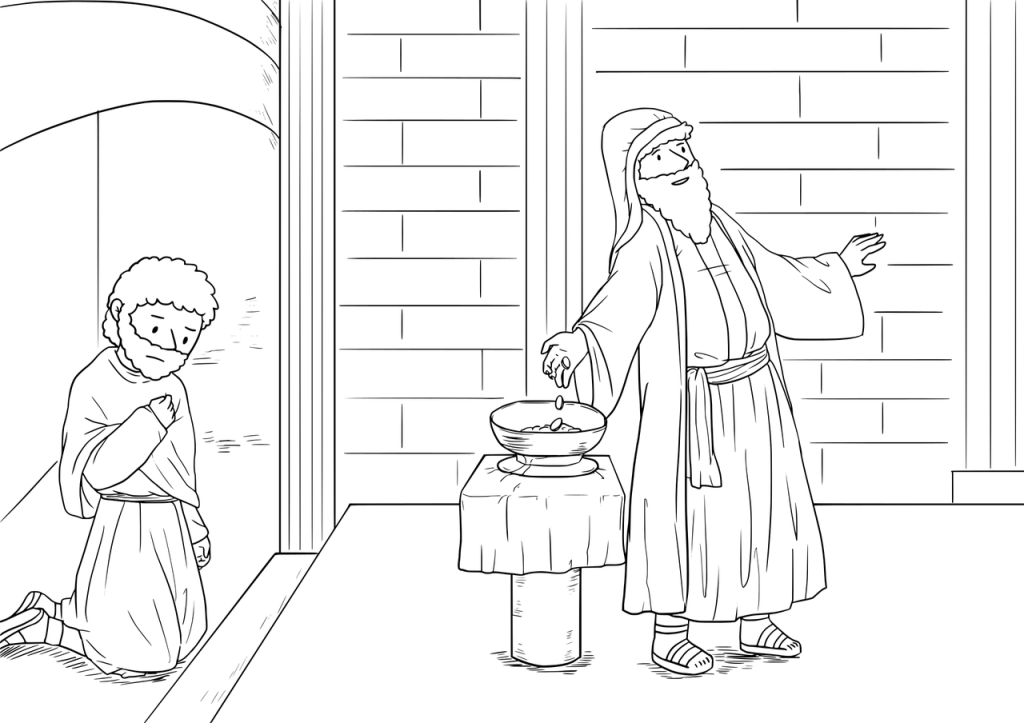

But Luke’s point goes even deeper. By missing the conversation, the Apostles missed a fuller understanding of what the glory of Christ meant. While a bright, fiery image of heavenly glory pervades the first reading, there is a darker side to the glory of Christ. It was foreshadowed way back at the Presentation, when Simeon spoke of Jesus, the “glory of Israel,” as a sign that will be contradicted (2:32,34). Now on the mountain, Moses and Elijah spoke of his exodus that he was going to accomplish in Jerusalem (9:31). And we know that Luke had an eye on the passion, death, and resurrection, for only he tells of Jesus on the road to Emmaus, saying: Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and enter into his glory (24:26)? John would confirm this throughout his own gospel account, where at the start of his passion Jesus said, Now is the Son of Man glorified, and God is glorified in him (John 13:31).

With that in mind, let us reconsider Peter saying, Master, it is good that we are here; let us make three tents… (Luke 9:33). The Transfiguration was a glorious “mountaintop moment” – something to capture and keep forever. God had spoken directly to them! Who wouldn’t want to hold onto that? We can relate; we all have mountaintop moments, times when God feels so close and it seems like He is speaking right to us. We want that wonderful feeling to never go away. However, we know that sooner or later, we will come down from the mountain, perhaps even into the valley. This fills us with dread, for it feels like a darkness where God is silent, far away, and all that glory a dim and distant memory.

Luke’s story of the Transfiguration teaches us that the glory of God cannot be reduced to such images. Our Lord Jesus Christ was every bit as eloquent and glorious on the Cross as he was at the Transfiguration, and his glory is as bound to us in our most intimate suffering as it is in our most contented joy. In that light, mountaintop moments and times of spiritual dryness are not feast and famine, but opportunities to grow closer to God; to revel in his wonder or to persevere in hope. In each one, God is challenging us to grow stronger, to love more deeply, and most of all to be spiritually alive and awake in the present moment, for that is where we live, where God meets us, walks with us, and feeds us with His grace.

Truly, it is good to be here.